… Estimated 334,000 people to face more crisis by March 2026

…2024/2025 Maize yield dropped by nearly 20 percent

More than a quarter of a million Basotho are currently facing hunger, with the situation expected to worsen as the lean season approaches.

According to the Lesotho Integrated Phase Classification (IPC) Acute Food Insecurity Analysis, released in October 2025, about 258,000 people, 17 percent of the rural population, are in crisis struggling to access enough food for survival.

The report paints a sobering picture of a nation grappling with compounding challenges which include erratic rainfall, dry spells, high food prices and livestock disease outbreaks that have collectively weakened Lesotho’s ability to feed its people.

By early next year, the situation is projected to deteriorate further, pushing an estimated 334,000 people, 22 percent of the population into crisis levels of food insecurity (IPC Phase 3 or higher).

This comes barely six months following Hunger Hotspots: FAO-WFP Early Warnings on Acute Food Insecurity report released in June where Lesotho was officially removed from the list of countries experiencing acute food insecurity.

Lesotho now joined Angola, Kenya, Namibia and Uganda, which were described to be showing signs of improvement after previously being identified in warnings.

In a joint statement, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the World Food Programme (WFP) said, “Angola, Kenya, Lesotho, Namibia and Uganda are no longer among the hunger hotspots, thanks to a combination of seasonal improvements, above-average agricultural production and effective response measures.”

Just over a month after Lesotho was removed from the list of countries identified as food insecurity hotspots by global agencies, a new regional assessment has revealed a concerning and contradictory reality: hunger in Southern Africa is worsening, and Lesotho remains far from immune.

Hardly a month after the removal from the Hunger Hotspot list, the SADC Regional Vulnerability Assessment and Analysis (RVAA) report, released in July 2025, estimated that 46.3 million people across seven countries — Botswana, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Eswatini, Lesotho, Madagascar, South Africa and Tanzania are projected to face acute food insecurity in the 2025/26 consumption year.

The SADC report noted that while Lesotho, alongside Tanzania and Eswatini, experienced above-average rainfall during the 2024/25 agricultural season, the country remains highly vulnerable to climate and economic shocks that continue to push many households into food insecurity.

For many Basotho, particularly in rural areas and peri-urban settlements, daily struggles to access affordable and nutritious food continue unabated and the IPC report confirms.

“Food access has become the greatest challenge. Even when food is available in the markets, many households simply can’t afford it,” reads part of the report, compiled by the Lesotho Vulnerability Assessment Committee with support from the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and The World Food Program (WFP).

Lesotho’s 2024–2025 agricultural season started with hope, the report noted, adding the rains that arrived in October and November 2024 encouraged timely planting, especially in the lowlands.

“…But optimism quickly gave way to despair when dry spells and heat waves scorched crops between December and January, the crucial growth stage.”

This climatic rollercoaster compounded by hailstorms birthed pests such as the Fall Armyworm. The country further experienced flooding early in 2025 which destroyed crops across most districts.

The report revealed that maize production, the nation’s staple, dropped by nearly 20 percent compared to the previous year.

It further noted that Lesotho’s total planted area increased slightly by 2.6 percent thanks to better access to fertilisers and seeds, however, extreme weather conditions wiped out much of the progress, leading to a national drop in yields.

Agriculture in Lesotho is not only about crops but a web of interlinked livelihoods.

The report indicates that the country’s rangelands showed some improvement, but livestock health has been hit hard by disease outbreaks linked to the prolonged dry conditions.

The report noted that in some districts, households were forced to sell off livestock to buy food. But even this coping mechanism is becoming unsustainable.

“High competition in the market has driven livestock prices down, leaving farmers with little to survive on.”

The IPC report further warns that these shocks have weakened already fragile income sources.

“Remittances, casual labour and crop sales remain the main sources of income for rural households, but declining employment opportunities and volatile prices have reduced their purchasing power,” the report said.

According to the 2024 Labour Force Survey, unemployment in Lesotho has climbed to 33.1 percent, with youth making up nearly 40 percent of those without work.

The three districts hit hardest by hunger are Maseru, Mafeteng and Mohale’s Hoek, all classified under IPC Phase 3.

Here, thousands of families are consuming fewer and less nutritious meals, often skipping food for days.

Districts such as Thaba-Tseka and Berea show relatively better resilience, with about half of households maintaining acceptable food consumption levels.

However, in Qacha’s Nek, Mokhotlong and Leribe, less than 40 percent of households are eating adequately, forcing many to rely on desperate coping mechanisms.

Nationally, the report finds that 44 percent of households are not yet engaging in negative coping strategies. But for the majority, survival now means borrowing food, reducing meal portions, selling productive assets, or taking on exploitative labour.

“The most vulnerable households are already resorting to measures that erode their future resilience and without timely intervention, the lean season could deepen hunger across all districts,” the report warned.

“From October 2025 to March 2026, Lesotho’s lean season is projected to bring deeper hardship. As household food stocks deplete, nine out of ten districts are expected to slide into Phase 3 (Crisis). Only Leribe is forecasted to remain “Stressed” (Phase 2).”

“High food and fuel prices are likely to persist, worsening the purchasing power of already vulnerable families. Even though South Africa, Lesotho’s main food supplier—is expected to record strong maize yields, imported food will still be too expensive for many,” the report noted.

It added that there is also a risk that heavy rains associated with a possible La Niña event could cause waterlogging, damaging crops during the next planting season.

“The number of people facing food gaps is expected to rise from 258,000 to 334,000. Without assistance, these households will resort to negative coping mechanisms to survive.”

In July 2024, the Lesotho Vulnerability Assessment Committee (LVAC) and Disaster Management Authority reported that approximately 699,000 Basotho, or one-third of the population, were food insecure for the 2024/25 cycle. Similarly, United Nations reports in September 2024 indicated that around 700,000 people would face hunger in the coming months.

Funding Initiatives to Address Food Insecurity in Lesotho:

- In September 2024, the UN allocated US$2 million from the Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF) to support drought-affected communities.

- The European Union pledged €200,000 (approximately LSL 4,030,000) in June 2024 to assist over 2,500 vulnerable families.

- According to LVAC, the government estimated a funding requirement of M1.149 billion to meet needs for 2024/25, an increase from M394 million the previous year.

- Earlier in mid-2024, the Disaster Management Authority (DMA) appealed for approximately M2 billion to finance immediate humanitarian aid and resilience-building programs.

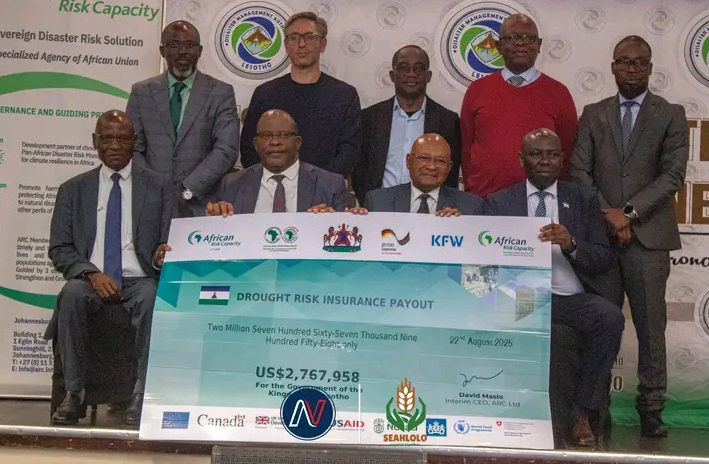

- In May and July 2025, a US$2.7 million (M50 million), one-off cash transfer programme supported by the Disaster Management Authority (DMA) and African Risk Capacity (ARC) provided relief to households affected by crop failure.

While the DMA/ARC intervention covered an estimated 86 percent of caloric needs for a portion of the affected population, analysts say it was too short-term to make a significant dent in the crisis.

Qacha’s Nek received the highest coverage, 19 percent of its rural population.

The IPC analysis calls for immediate humanitarian assistance, particularly for households in IPC Phase 3 or worse. But beyond emergency aid, it urges the government to scale up long-term resilience programmes such as catchment management, rangeland rehabilitation and livestock vaccination.

“The government must strengthen early warning systems and invest in community-based forecasting to prevent recurrent food crises,” the report recommends.

Despite the grim statistics, not all is lost. There are signs that Lesotho’s markets remain functional, ensuring food availability even when local production declines.

Water levels in major reservoirs are high, and winter cropping is expected to benefit from residual moisture and the government’s 70–80 percent input subsidy on seeds and fertilisers.